Veterans

The Willamette Master Chorus I sing with puts on a veterans concert each year. This weekend was the concert's 10th anniversary. It is because I participate in this concert that I've had to honestly grapple with what military service means - to me, to our world - and to ponder what it might mean to service members.

At some point at each of these concerts, we ask members who have served in each of our military conflicts and during peacetime to stand so we can thank them for their service. There is something visceral seeing normal folks around the room emerge suddenly as veterans from World War II, or Korea, or Vietnam, or ongoing military conflicts. It pulls history into the present. It puts human faces on contemporary political arguments. Here they are. The people we have asked, for reasons good or ill, to kill and perhaps die for us.

I do not need to romanticize their motivations to join, or lionize their actions while serving, to see the profound impact being in the armed forces has had on their lives and their identities. They have served, regardless of whether their political masters have treated their offers to sacrifice with as much respect and forbearance as they deserve.

I have had to get used to the mix of respect, anger and sadness I feel when my thoughts turn to veterans. It's uncomfortable to hold conflicting thoughts and feelings in my head at once, but I don't think comfort is the goal. This is perhaps the messiest part of our messy world, and I do not think I need to relinquish my hatred of war, or my anger at bellicose world leaders, to understand that our veterans have sacrificed for me. For us. And in my own, uneasy way, to be thankful for that.

Little Boxes

I understand the human penchant for categorizing things. We’re good at it. It's nearly automatic, and it's arguably a necessary survival skill. We cannot spend all of our time re-evaluating our understanding of every experience, every physical thing in the world, as though it were the first time. We need categories as a kind of cognitive shorthand – they let us wrap all we think we know about a set of things, place them in a little box, and add a label.

But when dealing with other people this quickly becomes socially corrosive. It is precisely because labels are shorthand – they stop us from new thought. We’ve already formed an opinion about the label the last time we used it, so the opinion just transfers to the next person, uncritically.

what is lost

When you use a label you are choosing, likely unknowingly, to not understand. All the nuance, the possibility that those labeled might have views that don’t fit into those neat little boxes, or haven’t fully figured out what they feel about an issue... that all goes away when the label shows up. We don’t see it anymore, and we stop thinking about it.

As you can imagine, this is most prevalent in politics and religion. You’re an X or a Y. The assumption goes that your label dictates your beliefs.

It’s a problem for the person labeled. But it is even more of a problem for the labeler. You deny yourself the opportunity for understanding. It’s quite likely that the person labeled either won’t hold quite the opinion you thought they did, or if they do, the reasons why they hold that opinion may be novel. You might learn something. Regardless whether it affects your opinion on the topic, it will very likely have an effect on your opinion of the person. I have had this experience myself. Looking for understanding is far more satisfying than the false certainty of those little boxes.

At a larger scale, labels inflame rhetoric and reinforce a sense of otherness. If someone labeled X disagrees with someone labeled Y, the easy reaction is "well, it must be because they're X and Y." Suddenly it becomes an issue of irreconcilable membership, not a nuanced discussion of values. Done frequently enough and labels can evolve into institutions, degrading the opportunities for collaboration and understanding.

From the other side of the looking glass, labeling yourself gives both others and yourself permission not to think deeply about why you hold certain opinions on a given topic. You put up a barrier to conversation and understanding - people will generally assume you have just adopted the party line. You may find that when you pull apart the positions and issues that are lumped into your label, you reach a point where don't really know the reasons behind your opinions on a certain topic. I know I've had to reevaluate the boundaries of certain positions I thought I had figured out. I have also seen this happen for other people, when I approach a discussion with the goal of understanding. If you can challenge them to think about it, you may both learn something.

Passenger Rail for Georgia

Attention to high-speed rail in the United States has picked up recently with the inclusion of funds for it in the newly signed stimulus bill. I've been exploring high speed rail plans in my corner of the country, and passenger rail in general, since reading JH Crawford's book Carfree Cities.

appropriate modes of transportation for given distances

As a form of passenger transport, rail can easily be the lowest energy per passenger-mile requirements. The 2008 US Transportation Energy Data Book places rail third (after van pools and motorcycles), but this is due to dismal ridership rates. It cites an average number of passengers per train at 24, which is less than even a bus can carry. Raising it to a mere 50 passenger average easily puts rail back at the top of the efficiency list (keep in mind that a typical train has capacity for 800 passengers). Also consider that new technologies and lighter materials can make the trains more efficient as well.

Rail also takes up far less land as compared to the multilane highways we rely on now to move large numbers of people (which, incidentally, typically do not move as many people as quickly as a well run rail line). And electrification of rail lines opens up the possibility of powering trains with renewable energy sources, compounding rail's climate and pollution advantages.

To get a drastic reduction in car-dependence for urban dwellers, you have to consider alternatives that provide reasonable autonomy and efficiency in place of automobiles. The good news is that in appropriately dense cities, and getting between them, rail provides a very good option.

appropriate modes of transportation for given distances

current high-speed corridor plans

In Georgia, there is very little passenger rail service. Inner metro-Atlanta has MARTA, and there are all of two meager passenger rail lines run by Amtrak: one in the north, and one along the coast. The passenger rail options only directly serve two of Georgia's 10 most populous cities. Plans for extending MARTA to Atlanta's outer suburbs have stalled time and again. There are thousands of commuters into Atlanta, Augusta and Georgia's other largest cities that have no viable alternative except to wade their way through traffic jams day in and day out.

There is a set of nationally designated high speed rail corridors proposed for Georgia. However, I feel that there are real problems with Georgia's current rail plans:

- The high speed rail only serves three of the state's top 10 most populous cities. It seems to avoid Athens (Georgia's 5th most populous city) on its way from Greenville, South Carolina to Atlanta for the sole reason of reusing the right-of-way already established by the current Amtrak route.

- It makes a stop in Jesup, with a population of 9k per the 2000 census. Again, there's existing infrastructure here (an Amtrak station), but high speed rail benefits from as few stops as possible, so you want to make those stops count.

Atlanta was founded as a rail-town. Certainly Georgia ought to be able to reclaim some of its legacy by building a modern passenger rail system for its citizens.

better serving urban population centers

Georgia's most populous cities

Atlanta: 519,145

Augusta: 192,142

Columbus: 188,660

Savannah: 130,331

Athens: 112,760

Sandy Springs(1): 97,898

Macon: 97,606

Roswell(1): 87,807

Albany: 76,939

Alpharetta(1): 65,168

Johns Creek(1): 62,049

Marietta(1): 58,478

Warner Robins(2): 48,804

Valdosta: 43,724

Smyrna(1): 40,999

East Point(1): 39,595

North Atlanta(1): 38,579

Rome: 34,980

Redan(1): 33,841

Dunwoody(1): 32,808

(1) exurbs of Atlanta (2) exurb of Macon

Part of the dilemma with providing effective rail service in Georgia is that the population is so spread out. The term "exurb", denoting the ever-expanding tracts of suburban living farther and farther from urban centers, could do with no better example than the metro-Atlanta region. Per 2007 figures (via Wikipedia), the city-proper of Atlanta is home to 519 thousand people, while an additional 4.8 million reside in the metro area, an area 62 times larger than the urban core. If where I live in Athens is any indication, even within the urban boundaries of most of Georgia's largest cities, the living arrangements are much more suburban than urban, making car ownership a near-necessity and hurting the chance for effective, ubiquitous public transit.

Riddle me this: is it easier to convince more than 100 thousand people to relocate their city to be closer to existing rail structure, or to put down new rail lines that would better serve existing urban centers? This is the question regarding the designated high-speed rail corridor currently proposed traveling from Greenville, South Carolina to Atlanta, bypassing Athens. First, consider that high speed trains can't use existing cargo rail; they will likely require upgraded or entirely new track to achieve the speeds desired, so the only real loss rerouting through Athens would be the existing right of way, not the actual infrastructure.

Next, consider that Athens is home to the University of Georgia, with a student body 34 thousand strong. Student populations typically both have low car ownership numbers but are also highly mobile as they travel regularly between home and school. I expect that a high speed rail link into the Atlanta Airport (and Atlanta nightlife), as well as to cities beyond Georgia, would be most welcome and heavily used by students. This, paired with more ubiquitous public transport within Athens, would likely encourage more students to forego bringing cars to school; increasing safety, reducing pollution and the ever-expanding need for parking space. It might also alleviate the immense floods of traffic that converge on Athens whenever the UGA football team has a home game. Now also consider that all but one of Georgia's most populous cities have significant student populations.

In order to maximize use of inter-city trains (high speed or otherwise) each destination city ought to prioritize improving their public transportation within the city. In turn, public transportation benefits from denser city structure. Making it easy to walk or bike from home to a transit stop, or from a transit stop to a destination, increases the chances that people will choose transit over personal cars. It is also an endorsement for mixed-use zoning, which brings destinations of all kinds closer to hand.

of population and density

What is a Car Free City?

In this section I refer several times to the urban design specified in the book Carfree Cities by JH Crawford. Essentially it calls for high-density, mixed-zoning districts strung out in a transit-oriented city topology. For more background, visit the carfree cities website, or take a look at how I mapped this idea onto Athens, GA.

If I had a free hand to reshape Georgia urban and transportation policy to get as many citizens car-free as possible, it would look something like this. First, I am going to advocate that all designated cities follow something approximating the reference design from the Carfree Cities book. To determine which cities ought to receive this treatment, we need to look at some population and labor numbers.

Of the 9.7 million people living in Georgia, over half of them live in the metro Atlanta area. The reference design suggests a population of 1 to 3 million per city; Notice that in the top cities table above many of the designated cities are actually exurbs of Atlanta. To fit the 5.3 million metro-area residents, well designate 3 "sister-cities" linked by an intercity rail loop as Crawford advocates when dealing with populations larger than is practical for the reference design. On a whim I've named the new sister cities after the counties where they reside, but you could also call them collectively ""Atlanta"; and consider each sister-city a borough, similar to how New York City is organized.

3 cities for Atlanta leaves some room for population growth. We'll look at the rest of Georgia in the same light. I've chosen to designate 10 cities for the 9.7 million residents. But not everyone will live in these cities. Some will live in more rural environs, either by choice or as required by their vocation.

From the categories listed in the Georgia Department of Labor 2004 statistics I've gleaned that only 11.9% of jobs in Georgia do not work well in an urban environment (Agriculture and Mining; I've also lumped in Manufacture, to take into account that this may include heavy industry that you would not want in a human-scale city). So, understanding that jobs and population count are not a 1:1 relationship, using a naive model we can start by mapping 12% of the population to the countryside, and count on 88% of Georgians to live in our 10 cities.

These numbers need some padding, though. First, we need to consider that if Michael Pollan is right, we're going to need a lot more hands on the land in order to produce our needed food crops. There are also plenty of jobs that need to be filled in small towns to support non-urban workers. I don't have a good sense of this, but lets take a stab and say that 20% of Georgians will live outside of cities, leaving us with 7.8 million urban residents.

With 10 cities on my map, that gives us a lot of head-room -- anywhere from 2.2 million to a whopping 22.2 million new people. Now, even considering that 2008 estimates of state population indicate Georgia gained 1.5 million new residents since 2000, this is probably excessive. But you will see that I chose to designate cities that are already well-established as major population centers, distributed across the state. The Carfree Cities model speaks of 2 million as a comfortable size and 3 million as a practical upper bound for the reference design; cities can grow into the model by adding districts or transportation loops as merited by population count.

revised rail corridors

So, back to rail. The map here identifies 8 cities across the state as major urban centers. The Atlanta area gets split into three cities to handle the burgeoning population there, bringing the total number of car-free cities to 10. The blue lines are what I feel are a better routing for the currently proposed high speed rail corridors. I've eliminated Jesup as a stop on the coastal route, and included Athens in the Northern Route from Greenville, South Carolina to Atlanta. I've also suggested we extend the inland route up to Memphis, Tennessee, another major urban center and destination in its own right.

I've assumed that it would also be necessary to include a more local service along these same rights of way, though probably not using the same tracks. Particularly while Georgia transitions away from suburban sprawl, and eventually to service towns that support rural vocations, a local service will be needed to make rail available to a larger number of stops than is practical with high speed rail.

Aside from the intercity ring between the three Atlanta sister-cities, the black rail lines represent rights of way and local passenger service between Georgia's other urban centers. Eventually it would be good to see high speed lines laid down along these routes as well.

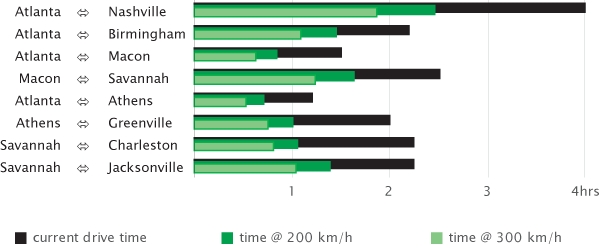

The speed advantages of high speed rail over car travel for the distances here are significant. 200km/h represents the lower bound of typical high-speed train speeds around the world, and more countries are starting to run trains at 300km/h or greater. I see no reason we should not have the ambition to operate the world's most effective public transit systems in this country.

conclusions

Transportation is a major element of national infrastructure in any nation. A good metric for setting national priorities is serving the broadest number of people. Among the various transportation options, public transit clearly meets this criteria. Road-building only provides transportation to those who have enough wealth to afford the large up-front costs of purchasing a vehicle, and the ongoing costs of fuel, maintenance and insurance. As we're seeing right now, easy credit isn't an answer to closing that gap either. And even could the economic hurdles be overcome, broadening the availability of car ownership to everyone runs up against environmental limits -- air pollution, increased storm-water runoff from more and wider roads, and global warming.

A recurring complaint about passenger rail in this country is that it seems impossible for Amtrak to make a profit. Consider, however, that the subsidies that go to rail programs are a pittance to the hidden subsidies propping up road and air use. The airlines do not solely fund the construction and maintenance of airports; States and the federal government care for the roads as the public good that they are. And yet somehow we expect rail to be self-sustaining. It is good to see signs that this country is starting to take rail travel more seriously; it is yet to be seen whether this will turn into a sustained commitment, or merely a brief dalliance with sound transportation policy.

ETech 2009: Hopes and Expectations

I've landed in San Jose to attend O'Reilly Media's Emerging Technology conference, thanks to the generosity of my family members, as a deferred 30th birthday present. The theme this year is Living, Reinvented. A large part of the premise of the conference is technology in the context of a world moving from abundance to constraints; how emerging technology can help us cope and thrive under the limits imposed on us by our environment, energy demands, and social constraints.

Looming large behind all of this is climate change. Yet the refrain I have heard many times over the last few years is that the technology for solving climate change is not new - not "emerging". I am not talking about adopting the back-to-the-land, "druid" mentality of Paul Saffo's druid - engineer continuum of climate change solutions. Rather by tapping into existing , sensible crop management, urban planning and public transportation we will find ourselves far along the path to sustainability.

I do believe the personalities behind ETech are genuinely concerned about environmental degredation and climate change; so I am not expecting a simple greenwashing attempt on their part. It is with more optimism than skeptecism that I look forward to the events over the next few days. I only hope that as a conference we do not simply slide back into fetishizing shiny techno-fixes.

Book Review: Beyond the Culture of Contest

As a telecommuting programmer and father of a two year old, I am not the most social of creatures. But I do have several family members who would likely describe themselves as social activists of one stripe or another. I recall one particular conversation on a late night a few years ago with a cousin of mine where I asked whether protest had ever achieved any real change. I am very sorry to say that I do not remember her answer, but by that time I had been exposed to ideas that suggested that there were more constructive ways of effecting change.

In that light, a few months ago I finished reading Beyond the Culture of Contest, by Michael Karlberg. I thought I’d write about it, as I feel it should be on the reading list of anyone interested in sociology or social change.

Power

After a lengthy discussion on what he means by the word “culture” in his title, Karlberg starts his thesis on a discussion on the dual nature of the word “power.” In common, everyday language, we use the word power to mean two very different things, depending on whether we are using it in an adversarial or cooperative context. In adversarial contexts, power denotes coercion, or between equals, a stalemate or at best a compromise. In cooperative contexts, power indicates constructive capacity – the power to accomplish a mutual goal.

Karlberg takes these two notions of power (which he shorthands as “power over” and “power to”) and takes them into the rest of his book to show how the currently dominant cultural institutions reinforce the “power over” mindset. He cites three broad areas of society where the culture of contest is assumed the natural state of things: in politics, the economy, and in legal disputes.

The Hegemony of Contest

For most people in the West, the idea that politics, the economy and legal disputes are competitions needs no explanation. From birth we are surrounded, unawares, by the language and practices of adversarialism. Karlberg demonstrates further how this “normalization” of competition is reinforced by commercial mass media (the “spectacle of conflict”), academia (grades as score-keeping, scholarly debate), and social protest (litigation, factionalization).

He points out that even in where we expect argumentation to produce useful results, as in scholarly discourse, that there are perfectly good ideas and suggestions that go unproposed simply because those who might bring them to the table are not comfortable with the character of the discussion. Rigor is still desired of course, but there are certainly ways to think critically about ideas without the adversarialism. And rather than dismiss these people as wimps, it is more useful to focus on the fact that we as a group are not benefiting from their potential contributions.

Karlberg does admit that there are times when the exigencies of a situation merit conflict in order to prevent disasters large or small. Yet he points out that such times are rare, and the need for adversarialism should not be seen as desirable; such actions can’t address much beyond the immediate crisis, and the residues of conflict can be corrosive to achieving longer-term goals.

Mutualism

But the book really starts to get interesting when Karlberg starts introducing us to living, working examples of the principles he is promoting in the book. It’s a glimmer of a way of interacting with each other as we might choose, rather than settle for what we’ve been told is the normal, natural and inescapable culture of self-interest and score-keeping.

The mutualistic practices he introduces us to come from a variety of sources: from cultural movements such as Feminism and Environmentalism, to general techniques such as Alternative Dispute Resolution. And he takes us on a comprehensive tour of the social implications of widespread mutialism as expressed in the Baha’i Faith.

The revelation of these practices as existent and successful was both stunning and inspiring for me. I’m conflict-averse at the best of times, but I had generally taken for granted that we lived in a rough and tumble world, even if I trusted that individuals are intrinsically good. That it is possible to choose another way, and a way that is still potent for solving problems and effecting change, gives me hope that I am not irreparably maladapted for making my way through life.

That’s not to say that mutualistic constructs are easy. Yet often the challenge lies in our development as individuals rather than struggle against external forces. Take, for example, the Baha’i practice of Consultation (collective decision making). It reads like a lifelong task in patience, selflessness, open-mindedness and trust. In brief:

- It seeks to build consensus in a manner that unifies constituencies rather than divides them

- It views diversity as an asset for decision-making; opinion and knowledge are widely solicited

- Upon sharing an idea, an individual has ceded it to the group; neither the flaws nor the merits of the idea reflect on the individual, and the individual must detach themselves from the ideas they offer.

- As an ongoing goal, participants try to moderate the tone and character of the discussion, in order to respectfully seek the best solution, not as a method to superficially paper over conflict.

- If a consensus cannot be found, a majority vote will be accepted; it is then expected that every individual will attempt to enact the decision in a unified manner, regardless of their vote. In this way the implementation of the decision may be evaluated solely on its own merits, without doubt as to whether individuals are passively or actively sabotaging it.

- By extension, ideas can be readily reconsidered if in their implementation they are revealed to be the wrong one.

I find it important that the challenges presented by such a model can develop qualities in each of us that a great many people consider unalloyed virtues. Compare them with a few of the adjectives we often hear associated with being effective in the province of competition: aggressive, cut-throat, ruthless, and dominating; qualities that are more likely to win you sycophants and enemies than friends.

Karlberg is careful to rigorously define the vocabulary with which he describes the subject of cultural interactions, and includes generous endnotes and a lengthy bibliography. In his quest for accuracy, though, Karlberg hews to a style that is dense, precise, and methodical. It is not light reading. I found I absorbed his ideas best piecemeal, leaving myself time to ponder their implications a few pages at a time.

Ultimately his thesis does not discard the notion of competition wholesale. A quick etymology search on the word uncovers the latin origin -– “Strive together.” Competition can be useful when its venue is limited, and done in the proper spirit. What Karlberg proposes is that adversarialism is not our natural social state, but rather only seems so because our current cultural institutions have accreted over time to reinforce conflict rather than mutualism. We have lost much of the togetherness, and are left with only the striving. He asks us for a certain mindfulness, so that we might maintain an awareness of when we find ourselves slipping into the memes of conflict, and what we might do to bring us closer to a world of mutualism.

Personally, I am starting to wonder if our habits of adversarialism developed at a time when the world was far less crowded. It was both possible and easier to separate yourself, spatially or socially, from those you did not agree with rather than work to live with each other in harmony. Now, there is no “going away” – you just wind up in someone else’s back yard. What would the world be like if we all started treating everyone we met as someone we would have to live with for the rest of our life?

I do not think, given the entrenchment of our current cultural institutions, that we can expect a shift to begin with any sort of top-down change. Indeed, such mandates may be fundamentally antithetical to mutualism, which governs by consensus rather than by edict. This is grass-roots stuff. It requires individuals to take it to heart – bring it into their families, their peer groups at work and in their community. Living in this way is a learning process, and you can’t learn by proclamation, only by practice.